It has been a long time since I learnt a new language. Instead of that I have rather been investing my time into creating the brain-friendly materials for the existing language courses. So in 2019 I decided to find out just what kind of experiences a learner with the ISONO device can make. To make this experiment worthwhile I decided to tackle Chinese, becauseI had it that this was a really tough language to learn for a European.

Learning Chinese

Since I started cooperating with ISONO we had been focussing on the most popular european languages: English, French, Spanish and Italian. The reason for that was that I can teach English and beginner’s French myself. After all, I grew up bilingual with English as second language. Even French I started to learn in a natural and fun way years before I could take classes at school.

My basic level Spanish got reactivated with a first experiment with the ISONO device. In fact, I am now actively practicing my Spanish whenever I can with my business partner Oliver Fuhr. He has been living and teaching German in Spain for more than 20 years. And guess what: Since I got certified as a Birkenbihl practicioner of language teaching I have even started learning Italian. But the most interesting test of the efficiency of the ISONO device, however, was the 9 month challenge to learning Chinese, that I took on in 2019.

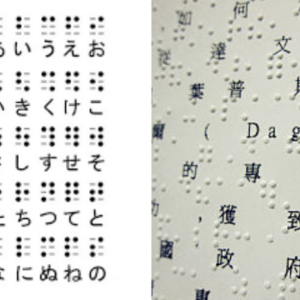

With the exception of some expressions such as „Thank you“, „Hello“ and „Good bye“ I didn’t understand any Chinese. Even though Japanese makes use of Chinese Characters, these have been radically shortened in the People’s Republic in the last century. So my knowledge of Japanese was not much of a help. At least for the beginning I decided to ignore the characters to avoid any confusion that might arise through false friends. Moreover, Chinese is a tone language: The tone of the different syllables is extremely important for the meaning. Not being a talented singer, I thought I would never be able to hear the differences, let alone pronounce them properly.

Supported by the ISONO device

So for my problems with listening and pronunciation I decided to test the efficiency of the ISONO device. I have been writing about Alfred Tomatis‚ discovery earlier on: „We cannot pronounce what we cannot hear „. Tomatis found out that a child already is exposed to its family’s native language long before it is born.

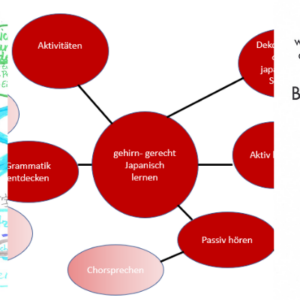

So I produced an audio from the material of a CD course containing nothing else but the Chinese dialogues. In doing so I heard these dialogues three times and already started to recognize a few words without understanding what was being said. In the next phase I used the ISONO device for one hour, twice a day to expose my body to Mandarin Chinese. That way I simulated how an unborn child is exposed to its mother’s voice. During that time I occupied myself with other things: working at my computer, being on the phone, listening to music, or cooking a meal…. Any other activity is allowed as long as the part of the body to which the divice is connected does not get wet. Water (or sweat) would disrupt the flow of the ultrasonic waves into the body. This so-called „passive listening“ was continued for exactly 29 days.

After that, I will go into the next phase of listening passively via the ears: listening to the audio via loudspeakers or earphones. Even now I still don’t need to understand what I am hearing. This would be imitating the situation of a Chinese baby listening to the members of its family.

Learning Like a Child

Does the support of the ISONO device itself already mean that I am learning a language like a child?

No, unfortunately that’s not quite enough. There are a few more mental prerequisites which I can learn from a child: Curiosity without prejudice, perseverance and the joy of learning. Let’s look at these qualities in more detail:

By „curiosity without prejudice“ I mean that I trust the ISONO device. That includes that I am not bothered by the transducers on my arm A positive attitude towards the device and the technology behind it is also part of the deal. I once had a client who told me that the device caused depression with her. She had not been able to cope with everyday life those few days she used it. Talking about this, she admitted that she didn’t like electronic devices in general and even had difficulties in using a computer. Another client even became aggressive and had to stop using the device after a few days. In both of these cases it might be possible that the negative attitude towards the device surfaced in the person’s mood. Henry Ford is reported to have said:

„No matter whether you think you can do it or you cannot do it: You will always be right.“

As for perseverence – more than 2 years after the experiment I can say, that I stuck to the routine for almost 9 months. I only gave up when it was time to start speaking to native Chinese speakers and to practice what I had learnt so far.

The Importance of a Positive Mindset

Have you ever whitnessed a small child occupying itself with something that it has no interest in? Actually, it is a sign that it is ready for school if it can sit still and listen even though it could be disctracted by something else.

The ISONO device will never teach us anything of which we are utterly convinced that we will never ever be able to do that. Such an attitude even shows that we aren’t even interested in learning this skill. The device works directly with our subconcious. On the one hand all the information is absorbed unfiltered. But on the other hand this information needs to be relevant to us. So it needs to be repeated over and over again. And during the activation phase it will have to be integrated into our every day life. As long as we are not interested at all, the information is not retained and the door to that knowledge and skill remains closed.

Trust the Method

So if we want to be supported by the ISONO device, we need to trust the technology. If we do so, we can even use it to our advantage by using the affirmations on the device, such as „Concentration“ or „Learning is fun“ These are also available in English. We can even create our own affirmations, record them on the device and use them as a prelude to the language audio.

I once had a client whose progress in learning English was very slow even though he was using the ISONO device extensively. He still trusted the device and the technology. One day we talked about his thoughts about the English language. He spurted: „It’s all mumble jumble to me! I don’t like the sound of it at all!“ On top of that he didn’t like the Americans‘ culture. However, he wanted to travel to Scotland and talk to the people there. Finally we had found these hindering thoughts. As soon as he started breaking the power of these thoughts with affirmations, it became easier for him to remember the vocabulary and sentence structures. It was only now that the ISONO device was able to support him, as well as the brain-friendly methods I had been using from the start.

How Do I Think About Chinese?

Based on these experiences I looked closely at my thoughts about the Chinese language. It was already at university that I had had the choice between studying Chinese or Japanese. At that time I had been fascinated by the classical culture of China, as well as the many different cultures living in that vast state. However, the writing system and the tones turned me off. To me Japanese seemed easier at that time. Today I have inspiring conversations with Chinese and Taiwanese friends (in English and German) and have spent four days in Taipeh, where I could communicate via the characters but I could not talk with the people.

In the mid-1990s very few people spoke English in Taiwan and I had planned to do the tour of the island, hoping to communicate in Japanese with the older people of the minorities. Sitting on the plane back to Japan I was looking forward to a country where I could speak with the people and could make myself understood. At that time I vowed to come back after having learnt at least the basics of Chinese. So with this experiment I was laying the foundation to fulfilling this vow.

So once I had found an access to my intrinsic motivation it was important to see: I did not learn Chinese because I wanted to prove something to others. I was learning with curiosity and because I had the goal of visiting at least Taiwan once more.